But the gospel is also inextricably bound up in culture. The plain news of Christ comes to us encoded in language. Christ, the eternal Word, became incarnate. And, imitating Christ, the apostle Paul sought to “become all things to all people, that by all means I might save some” (1 Cor. 9:22).

Missionaries today entering unreached contexts have a daunting task, transposing transcendent truths into new words, shapes, and sounds for hearers with no prior basis of biblical understanding. Like Paul, the contemporary missionary must be armed with the simple, effective Word of God, but he must wield it in such a way as to be presentable and understandable by peoples of all backgrounds and walks of life. This is the critical work of healthy contextualization.

How can a missionary accomplish such an enormous undertaking? By prioritizing acquisition of the culture and language of the people he serves. Only by understanding the worldview, traditions, and tongue of our hearers can we hope to present the gospel in such a way as to be heard.

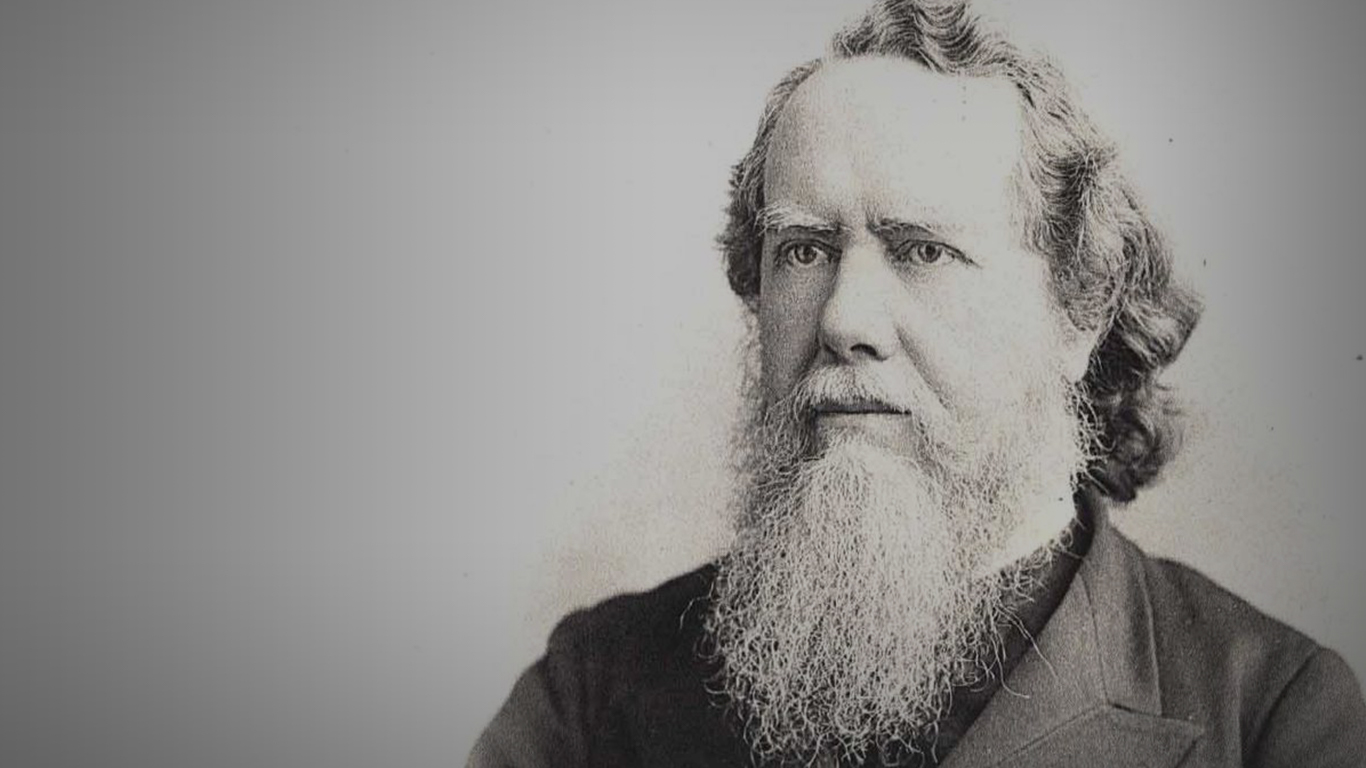

James Hudson Taylor (1832-1905), pioneer missionary to China’s interior and founder of the China Inland Mission (known today as Overseas Missionary Fellowship), was among the first modern missionaries to embody this cross-cultural spirit. As Taylor penned in an 1850 letter: “…[M]issionaries should be men of apostolic zeal, patience and endurance, willing to be all things to all people.” A survey of Taylor’s life and ministry reveals the critical importance of faith, prayer, and an unwavering commitment to an embodied, missional presence in a culture in which the gospel is considered foreign.

Saved to Serve

Born and raised in Barnsley in South Yorkshire, England, Hudson Taylor had the privilege of an ordinary, blessed Christian household and upbringing. His father, James Taylor, was a Methodist preacher, and his mother Amelia herself was a woman of intense spiritual devotion. But though acquainted and even enthused with the Christian faith at an early age, a teenage Taylor later found himself hardened by the deceitfulness of sin and unable to save his own life through religious strivings. But at 17, a skeptical Taylor began reading a gospel tract (titled “Poor Richard”)—which he fully intended to read only as a compelling story, skipping over the spiritual parts—and was cut to the heart by the expression “the finished work of Christ.” Realizing that salvation was a free gift which he could only but receive, Taylor was miraculously converted. Only later did he discover that his mother, hours away on a trip, had been burdened to pray intensely for him for multiple hours. About the time he was converted she suddenly felt a sense of relief, knowing that the Lord had granted her petition. Taylor described the whole unfolding of events as follows:

I sat down to read the little book in an utterly unconcerned state of mind, believing indeed at the time that if there were any salvation it was not for me, and with a distinct intention to put away the tract as soon as it should seem prosy… Little did I know at the time what was going on in the heart of my dear mother, seventy or eighty miles away. She rose from the dinner-table that afternoon with an intense yearning for the conversion of her boy… She went to her room and turned the key in the door, resolved not to leave that spot until her prayers were answered. Hour after hour did that dear mother plead for me, until at length she could pray no longer, but was constrained to praise God for that which His Spirit taught her had already been accomplished—the conversion of her only son. I in the meantime had been led in the way I have mentioned to take up this little tract, and while reading it was struck with the sentence, “The finished work of Christ.” … Immediately the words “It is finished” suggested themselves to my mind. What was finished? And I at once replied, “A full and perfect atonement and satisfaction for sin: the debt was paid by the Substitute; Christ died for our sins, and not for ours only, but also for the sins of the whole world.” Then came the thought, “If the whole work was finished and the whole debt paid, what is there left for me to do?” And with this dawned the joyful conviction, as light was flashed into my soul by the Holy Spirit, that there was nothing in the world to be done but to fall down on one’s knees, and accepting this Saviour and His salvation, to praise Him for evermore. Thus while my dear mother was praising God on her knees in her chamber, I was praising Him in the old warehouse to which I had gone alone to read at my leisure this little book.

Not only this, but Taylor later discovered a journal entry from his sister (also Amelia), in which she had committed some weeks prior to pray for her brother three times daily until he was converted. Through this experience, not only did Taylor come to see the extraordinary power of the cross, but also the power of ordinary prayer—something upon which he would stake his entire life.

A New Mission

As is the experience of many Christians, months after his conversion Hudson Taylor hit a spiritual plateau, his zeal for evangelism waning. Convinced by now, however, that prayer was a matter of simple transaction with God, he withdrew into private prayer, and received the distinct, settled sense that he was to give his life to ministry in China—a land for which he had already been burdened as a child, as he recounted vividly the prayers of his parents for more missionaries to be sent to the distant, unreached land.

But unlike modern youth for whom the next mission trip to a place like Tijuana is a short bus or plane ride away, for Taylor to consider becoming a missionary to China was to envision a task altogether shrouded in mystery. With the bloody Taiping Rebellion yet barely underway, inland China was still unreached by foreigners, and the few reports of China that had made it to England came by way of observations made in port cities. Yet Taylor’s conviction had been no fleeting impression; it was one which proved itself the driving force in virtually all of his conscious pursuits from that moment forward. Immediately he started distributing gospel tracts to all those around him and acquired a copy of China: Its State and Prospects by the Congregationalist missionary Dr. Walter Medhurst of the London Missionary Society. Taylor wanted to absorb as much information as he could about the land of the red dragon.

Even at this early stage, with few and meager resources, Taylor committed himself entirely to the task of preparing for culture and language acquisition. He could not afford a Chinese grammar or dictionary, but he was able to secure a copy of Luke’s Gospel in Mandarin—a sort of Rosetta stone that unlocked to him a significant Chinese vocabulary. By carefully cross-referencing often-repeated Chinese characters with what appeared to be their English equivalents, he was able to decode more than five hundred Chinese characters.

In addition to his independent studies in Mandarin, the official governmental language of China, Taylor also took it upon himself to study biblical languages, medicine, and other subjects to become the sort of versatile generalist who could both survive and minister effectively in a foreign land. Of this preparation, he wrote in a letter:

I have begun to get up at five in the morning and so find it necessary to go to bed early at night. I must study if I mean to go to China. I am fully decided to go and am making every preparation I can. I intend to rub up my Latin, to learn Greek and the rudiments of Hebrew, and to get as much general information as possible. I need all your prayers.

Not only was Taylor’s training linguistic; he also proactively prepared for the rigors of a subsistence lifestyle in a foreign land. He traded his feather mattress for a hard bed, took up exercise in the open air, and carefully limited his food intake. He was also convinced that, to be “all things to all people,” a good missionary should possess a skill or trade through which to provide earthly benefit to his hearers and gain trust for the propagation of the gospel. In 1851, at the age of 19, Taylor relocated to Drainside—an impoverished, dour, and noisy neighborhood on the outskirts of Kingston upon Hull, named for the murky tide that would carry away the garbage that accumulated between its rows of cottages—to train in medicine. Drunkenness and sickness were both common in this slum, and Taylor devoted himself to both any open-air preaching and mercy ministry he could fit into his spare time when not serving as medical assistant to Robert Hardey.

In this context God conditioned Taylor—and Taylor conditioned himself—for a life of faith. On one occasion, a Drainside man approached Taylor and begged him to come and pray for his dying wife, as the local priest had wanted to charge too much for the visit. Upon entering the room of the ailing woman, Taylor saw that they could avert starvation if he only surrendered his last half-crown coin burning a hole in his pocket. But Taylor, now living off small portions of simple foods like rice and oatmeal, did not feel he could part with his last remaining resources. Further, Dr. Hardey was prone to forget to pay Taylor his salary, and Taylor desired not to remind Hardey of the matter but rather to trust God to bring his salary to his employer’s mind, seeking to stretch his muscles of faith. After praying a rather empty prayer with the family, the husband turned to him. “You see what a terrible state we are in, sir; if you can help us, for God’s sake do!” he charged. In what Taylor felt to be an agonizing crisis of faith, he finally succumbed to the conviction of the Holy Spirit and revealed the half-crown, immediately feeling a sense of relief. Taylor went to bed penniless but filled with peace, and the next morning awoke to an anonymous delivery: an envelope containing a half-sovereign (five times the value of the coin he had given away). Experiences like this not only exercised and built his faith but prepared him for the discomfort and risk-taking necessary to immerse himself into Chinese society as a gospel worker. Thus, he resolved “to move man, through God, by prayer alone.”

Open Doors?

Though early in his studies, Taylor found the door to China opening rather quickly and providentially—at least, as it seemed. And further, the very circumstances under which that door was beginning to open are themselves a lesson in the importance of proper contextualization.

News had come to Britain of the Taiping rebellion, which appeared to outside observers to represent a significant Christian movement sweeping across China all on its own. Hong Xiuquan, the Taiping leader, propagated his own version of the Ten Commandments throughout the land. It seemed that, in spite of the spiritual resistance of the existing Qing Empire, China was now “open.” Thus, men like Karl Gützlaff, the first German Lutheran missionary to China, became convinced that China could be rapidly evangelized, and built the Chinese Evangelization Society (CES) on partnerships with indigenous works in the country. Gützlaff became an evangelist throughout England, sharing both the spiritual need and exciting opportunity that existed in China, and himself became one of the very earliest Protestant missionaries to adopt Chinese garb in the interest of contextualization.

But not all that glitters is gold, and only over time did the true nature of the Taiping rebellion become clear to the Western world: Hong Xiuquan was a radical insurrectionist and a cult leader. Hong had read a long tract by the missionary Liang Fa, a disciple of the pioneer Presbyterian missionary Robert Morrison, but was himself left completely undiscipled himself, encountering just enough of the content of the gospel message to pervert it for gain. Hong styled himself a son of God and brother of Jesus Christ, and his “Heavenly Kingdom” movement and the resulting violent uprising led to some 20 million deaths—a development no doubt responsible for modern China’s continued suspicion toward Christianity in any form to the present day. Had the gospel workers within reach of men like Hong focused more on intentional, long-term discipleship in an appropriately contextualized manner—cutting through the haze of Confucianism and making biblical teaching more understandable in an Eastern context—perhaps the misled, barely-evangelized people could have been saved from grave error and war.

In time, the Qings put down the resistance, and China became increasingly closed to foreigners and to the faith. The CES itself would prove equally short-lived; by 1865, a dismayed Gützlaff was forced to disband the society, having been led astray by deceptive indigenous “ministers” whose exaggerated accounts of the spread of the gospel at their hands had in fact served only to line their pockets with opium money—another striking parable about the importance of foreign missionaries mastering culture, customs, and language.

But in 1852, before the true colors of Hong’s deceitful ministry had been revealed, the CES approached Taylor with an offer to pay for his medical studies in London in preparation for overseas service. And in 1853, before having even completed his studies, Taylor became so convinced by the optimistic reports of the Taiping rebellion and their successful invasion of Nanjing that he was compelled to set sail for China with no further delay. On September 19, 1853, the 21-year-old Taylor boarded the Dumfries in Liverpool headed for Shanghai—the vessel’s only passenger.

Shanghaied

On the way, the Dumfries nearly shipwrecked twice, and each occasion proved a powerful exercise for the building of Taylor’s faith and prayer life. Afflicted as many often are from prolonged periods of travel, Taylor’s spirits were kept high by the frequent opportunities for ministry with the crew, who, though open to spiritual conversation and often eager to listen, never seemed to reach a point of conversion.

Taylor had readied himself for all the typical challenges of missionary life, but he hadn’t prepared to walk into a warzone. When the Dumfries finally ported in March 1854, all of the missionary contacts he had been given turned into dead ends—including Dr. Medhurst himself, who had fled to the consulate because of the conflict. Each night, the sound of fighting could be heard outside his window, and his medical expertise was soon tested as he began treating devastating battle injuries as serious as cannonball trauma. Yet in God’s providence, Taylor had happened across other European missionaries who were boarded by Dr. Lockhart, a worker with the London Missionary Society.

Taylor’s heart for contextualization was manifest in the standard of living he maintained in Shanghai when under the care of the CES. A new missionary unit, a Dr. Parker and his family, was sent by the mission to serve alongside Taylor, with little in the way of advance preparation, financial or otherwise. When Parker, his wife, and three children arrived, they stumbled upon what by any English standard would have been inadequate living conditions—a mere six chairs, mismatched dishes, and other scanty provisions owing to Taylor’s having been substantially underpaid by the CES. But for Taylor, who had committed himself not to complain about the level of salary until it became apparent that CES had made no provision to get the Parkers their payments, this was as much a decision of frugality as it was a desire to not enjoy a standard of living vastly superior to that of the Chinese nationals surrounding him.

But his piecemeal language preparation had not been altogether adequate. In this fragile state of mind, unable to speak or understand the dialect of the people in Shanghai and witnessing on all sides to the suffering and wounds of war, Taylor found himself in a position much like that of the prophet Jeremiah: “If I say, ‘I will not mention him, or speak any more in his name,’ there is in my heart as it were a burning fire shut up in my bones, and I am weary with holding it in, and I cannot” (Jeremiah 20:9). Burdened by his inability to openly speak of Christ, an activity to which he had been accustomed, he devoted himself still more to learning the language, even neglecting personal devotions. He wrote:

My position is a very difficult one. Dr. Lockhart has taken me to reside with him for the present, as houses are not to be had for love or money…. No one can live in the city, for they are fighting almost continuously. I see the walls from my window… and the firing is visible at night. They are fighting now, while I write, and the house shakes with the report of cannon.

It is so cold that I can hardly think or hold the pen. You will see from my letter to Mr. Pearse how perplexed I am. It will be four months before I can hear in reply, and the very kindness of the missionaries who have received me with open arms makes me fear to be burdensome. Jesus will guide me aright. … I love the Chinese more than ever. Oh to be useful among them! …

The cold was so great and other things so trying that I scarcely knew what I was doing or saying at first. Then, what it means to be so far from home, at the seat of war, and not able to understand or be understood by the people was fully realized. Their utter wretchedness and misery, and my inability to help them or even point them to Jesus, powerfully affected me. Satan came in as a flood, but there was One who lifted up a standard against him. Jesus is here, and though unknown to the majority and uncared for by many who might know Him, He is present and precious to His own.

He later described to his sister Amelia the vexation of soul produced by his five hours per day (on average) of language study, which crowded out his time in Scripture study and prayer: “At first I allowed my desire to acquire the language speedily to have undue prominence and a deadening effect on my soul.”

Dressing the Part

Taylor recovered from this inner spiritual affliction, meditating more upon the promises of God while continuing to devote time to learn the customs and tongue of the Chinese. In February 1855, he began to make his first evangelistic journeys—which were to total more than ten in just two years—but because of political turmoil and conflict throughout the country, Taylor returned to Shanghai. He traveled up the Yangtze River, preaching the gospel and sharing medical supplies in more than 50 villages, several of which had never seen a Protestant missionary before. In August, he left Shanghai for Ningpo to the south—feeling no doubt disillusioned by the apathy, cynicism, and lack of self-discipline among the missionaries he had encountered in Shanghai—and it was around this time his ministry took on one new, important characteristic.

Throughout his preaching trips, Taylor had been met in part with a rather limited reception, earning himself the name “black devil” among the Chinese because of the long, black overcoat he often wore. The trappings of his European culture were proving a hindrance to the message he sought to deliver. In response, Taylor embraced the example of Gützlaff, trading his English garb for baggy pants and calico socks, a wide-sleeved robe, satin shoes, and a traditional Manchu queue (a long braid of hair on the back of the head, accompanied by a shaved forehead) which was the standard among Chinese men during the Qing Dynasty. Though drawing criticism from other missionaries and the Chinese themselves, Taylor’s embrace of the native clothing style gained him a distinct advantage. No longer did he immediately attract the quizzical stares of indigenous passersby; he blended in. In time, this would become normal practice for all the missionaries serving with Taylor’s China Inland Mission (CIM), of which Taylor called Gützlaff the “grandfather.”

And not only did Taylor look the part; he also sounded the part. On one occasion in May of 1855, preaching in and around the region of Changshu, his hearers understood his Chinese speech so well that they remarked, “The foreign devil language is almost the same as our own.”

With this contextualizing edge, Taylor set out on his first journeys to inland China, a strategy considered extremely risky and uncommon even among the existing Protestant missionaries in the country. He joined forces with Presbyterian missionary William Burns, who also began to adopt the national style of dress. The two shared akin spirits, in a fashion reminiscent of Scripture’s description of David and Jonathan, and both sensed the call of God to minister in Shantou, more than 800 miles to the south of Shanghai. But by summer of 1866, having encountered limited success, the two agreed on a course of action. Taylor reluctantly returned to Shanghai to secure more medical supplies—only to learn that a fire had destroyed the supplies they had stored, and that meanwhile Burns had been imprisoned. In the fall, Taylor was robbed of virtually all his possessions, his only redeeming grace being his adoption of the Chinese garb which prevented him from being further wronged. Also around this time, Taylor’s romantic interest back home, to whom he wrote frequently, had declined his marriage proposal, and the CES had informed him that there were no more funds for his ministry. Taylor was in dire straits.

Yet encouragement came in the form of a letter from Taylor’s hero in the faith, George Müller, the famed English evangelist and minister to countless orphans, expressing his support. The overflow of this encouragement in 1857 prompted Taylor to make the decision—rather than cutting back the work of the ministry itself due to a lack of funding from the CES—to establish the “Ningbo Mission” with no backing from a church, denomination, or existing organization, but only the faith in the promises of God to sustain it.

The next year, Taylor married Maria Jane Dyer, a missionary in China and daughter of the Reverend Samuel Dyer, and became acquainted again with suffering when their first child died. In 1859, their daughter Grace was born, and they continued diligently in ministry together until 1860, when, for health reasons, Taylor (beset with poor health his whole life) and his young family took their first furlough back to Great Britain.

From Goer to Sender

Taylor’s zeal for the lost masses in China didn’t wane when he returned to Europe. He and Maria developed a publication later called China’s Millions, which became a catalyst for the eyes of many to be opened to perceive the massive spiritual need in the great oriental nation. During this time period, Taylor befriended Charles Spurgeon, and preached frequently as a mobilizer seeking to spur Britons to pray, give, and themselves take the gospel to China. The Taylors had more children, including another daughter, Jane, who died at birth in 1865.

But Taylor couldn’t stay still. That same year, during a time in fellowship with the Lord on Brighton beach in East Sussex, on the south coast of England, Taylor was burdened that more well-qualified, diligent, pioneering missionaries were needed in China’s unreached interior. In prayer, he arrived at a goal, and wrote in his Bible: “Prayed for the 24 willing, skillful laborers at Brighton, June 25, 1865.”

In this moment, the CIM was finally born. God quickly provided both funds and all 24 laborers. The new mission was marked by several traits, including its commitment to faith support and interdenominationalism, but chief among them was its distinct emphasis on the indigeneity of the Chinese church. Taylor firmly believed that a truly culturally Chinese church was the only means by which the gospel could take root in a country as ancient and unique as China—a belief that has been vindicated up to the present moment in the explosive growth of the Christian movement among the Han Chinese and minority populations. Taylor expressed this desire on one occasion: “Let us in everything not sinful, become like the Chinese, that by all means we may save some.”

As a result, all the missionaries of the CIM adopted the same shaven forehead, queue, and Chinese apparel worn by men like Hudson, Burns, and Gützlaff before them. Healthy contextualization was a key commitment of new CIM missionaries. And so, bound together in this commitment, the “Lammermuir Party,” Taylor’s group of 18 missionaries including himself and Maria, departed from Shanghai onboard the Lammermuir, a British tea clipper. Surviving a harrowing voyage involving near shipwreck and two typhoons—all while the passengers faithfully evangelized the 30-plus crewmen—the party finally made port in September of 1866, delivering its precious cargo to a continent swooning with unreached masses.

Through Many Tribulations

The unique practices of the young CIM missionaries with regard to dress and style did not go without criticism from observers. The predominant school of thought among Western missionaries maintains that Western forms, even cultural ones, should be maintained. Taylor not only broke this taboo but instructed the women as well as the men in his group to follow in the same sort of practice, drawing much suspicion from the other foreign nationals residing among them. But aside from these controversies, other difficulties plagued the young mission. Dissidents rose up who questioned Taylor’s untested leadership. Yet again, the Lord ordained a bitter providence for the missionary statesman which served to advance his purposes. The Taylors’ eight-year-old daughter Gracie died of meningitis in August of 1867, ultimately uniting the team as they observed Taylor’s selfless service.

Nevertheless, trial continued to afflict the ragtag team of workers. Looted by rioters as they ministered in Yangzhou, the CIM group soon had to contend with British calls for the withdrawal of all foreign workers from China due to the political instability. Yangzhou suddenly became unfriendly toward Westerners, and donors in Great Britain—having heard only perversions of the real accounts from the faraway land—began withdrawing their support. A gift of approximately $10,000 from Müller more than made up for the losses and gave Taylor the encouragement needed to press on.

In the course of these events, Taylor also made a spiritual breakthrough. Calling this realization the “Exchanged Life,” he discovered that all his striving for strengthening and communion with God were vain labors from which he was to cease. Instead, Christ was calling him to rest in his constant presence. “I have striven in vain to abide in Him, I’ll strive no more. For has not He promised to abide with me… never to leave me, never to fail me?” he wrote. No longer under the immense psychological pressure of having to consciously recognize the presence of God with him, Taylor was impressed with a deeper awareness that God was present whether he sensed him or not. For all the hardships he had endured and would yet endure, this epiphany more than supplied the deep, settled strength he would need. Unlike so many of the “higher life” experiences of other Keswick theologians of his day, this particular experience bore lasting fruit in Taylor’s life, visibly affecting both his demeanor and the entire spirit in which he approached work and rest for the duration of his life. Taylor’s “Exchanged Life” had been no dithering spiritual mountaintop experience, but a well-marked crossroads in the ongoing, straight, narrow path of discipleship.

Yet tragedy would strike again indeed. A few years later, in 1870, another of the Taylor’s children passed away of malnutrition just weeks after birth—his fourth child to die. Baby Noel’s death was followed three days later by the passing of Maria herself from tuberculosis at the young age of 33, after 12 years of marriage and having born Hudson eight children (with one stillborn). Taylor sent his other children to England for safety. But the trauma piled on, and within a year the grief had not only taken a great toll on Taylor’s mental wellbeing but on his physical health as well.

Although Taylor had gained relief in his attitude shift through the “Exchanged Life” realization, he was not invulnerable to all human weakness. When William Berger, the British home director of the CIM, had to step away from his role for health reasons, Taylor also conceded the necessity of his return to England in 1871 for much-needed rest and healing.

The following year, Taylor married Jennie Faulding, a fellow missionary. The two left for the mission field again in October of 1872, leaving their children in England for safety and to be raised by the mission secretary Emily Blatchley. This brief note of triumph was interrupted by the grief of Jennie’s bearing stillborn twins in 1873, and when Blatchley herself passed away in 1874, the two quickly returned to England to care for their children.

From England, Taylor continued to mobilize, exerting influence in the life of the Cambridge Seven (including such notables as C.T. Studd), who went on to serve in China. Taylor appealed in prayer for 18 new workers to open more doors throughout China’s nine unreached provinces in the interior. In 1876, with the signing of the Chefoo Convention which made inland China accessible to Christian workers, Taylor was able to return with the new workers—but left Jennie behind to tend their children. She was able to join him two years later, and the CIM continued to grow in part through her efforts to mobilize more female workers. By 1881 the CIM boasted 100 workers, and Taylor and the team resolved to ask the Lord for another 70.

By 1885, the mission had grown to 225, drawing support from 59 churches. To saturate China with the gospel, another 100 workers were needed—and by the end of 1887, 102 new missionaries had been commissioned and sent. The year after, Taylor continued his rigorous mobilizing ministry by preaching from D.L. Moody’s pulpit in Chicago, resulting in the church’s decision to support the CIM.

Finishing the Race

Though the CIM enjoyed explosive, miraculous growth in fundraising and recruitment—the direct outworking of Taylor’s intimate prayer life—Taylor’s final years were as marked with brokenness and trial as his ministry itself had been. The Boxer rebellion, a violent Qing-sponsored uprising targeting foreigners, claimed the life of more than 200 Western missionaries living in China in 1900, and 58 were workers with the CIM—not to mention the 21 children whose lives were claimed. News of the losses crushed Taylor, but he refused to react vengefully or accept any payment for their losses, making an incredible statement through his Christlike behavior to many including the Chinese themselves.

Health concerns led him to retire to Switzerland, and in 1902 Taylor turned over leadership of the mission to D.E. Hoste. In 1904, Jennie died of cancer at 60 years old, and in the year following Taylor set off for his eleventh and final voyage to China. Taylor’s travels took him to Changha, the capital of the Hunan province—the most impenetrable of the nine unevangelized provinces. He died peacefully and quietly on June 3, 1905 in the home of his daughter-in-law, not long before the country would again close under communist rule later in the 20th century. Nevertheless, in just two years from then China would see more than 800 Christian missionaries ministering in its interior.

Conclusion

In closing, much can be learned from Taylor’s ministry, including the power of prayer, the sovereignty of God in suffering, and the vast importance of gospel zeal. But we must not overlook the way in which Taylor’s immersion in the Chinese language and culture became an consistent thread throughout his life and ministry—and not the sort of modern hyper-contextualization we envision today that compromises doctrinal content in the name of cultural accommodation.

Taylor regarded himself as following the example of Paul who, in 1 Corinthians 9, sought to be “all things” to all people in order to save as many as possible. And so it was none other than his acquaintance Spurgeon who wrote of the pioneering missionary statesman:

If Paul met with a Scythian, he spoke to him in the barbarian tongue, and not in classic Greek. If he met a Greek, he spoke to him as he did at the Areopagus, with language that was fitted for the polished Athenian.

He was all things to all men, that he might by all means save some.

So let it be with you, Christian people. Your one business in life is to lead men to believe in Jesus Christ by the power of the Holy Spirit, and every other thing should be made subservient to this one object. If you can but get them saved, everything else will come right in due time.

Mr[.] Hudson Taylor, a dear man of God, who has laboured much in inland China, finds it helpful to dress as a Chinaman and wear a pigtail. He always mingles with the people, and as far as possible lives as they do. This seems to me to be a truly wise policy. I can understand that we shall win upon a congregation of Chinese by becoming as Chinese as possible; and if this be the case, we are bound to be Chinese to the Chinese to save Chinese. (The Soul Winner, 214)

Taylor accommodated himself to the culture, customs, dress, and speech of the people, but the word of the cross remained uncompromised and unembellished. And in this regard, there are no shortcuts.

Further Reading

- Hudson Taylor: Deep in the Heart of China by Janet and Geoff Benge

- Hudson Taylor in Early Years: The Growth of a Soul and The China Inland Mission: The Growth of a Work of God (two-volume set) by Howard and Geraldine Taylor

- Hudson Taylor’s Spiritual Secret by Howard and Geraldine Taylor