In choosing to follow the call of missions, they left behind family, friends, and the familiarities of home for unfathomable hardships including, starvation, sickness, oppression, even death.

But that is not where the story ends.

God used their sacrifices to not only to accomplish a mission but to leave a legacy for the name above every name: Jesus Christ.

Prisoners of War (The Philippines: 1942-45)

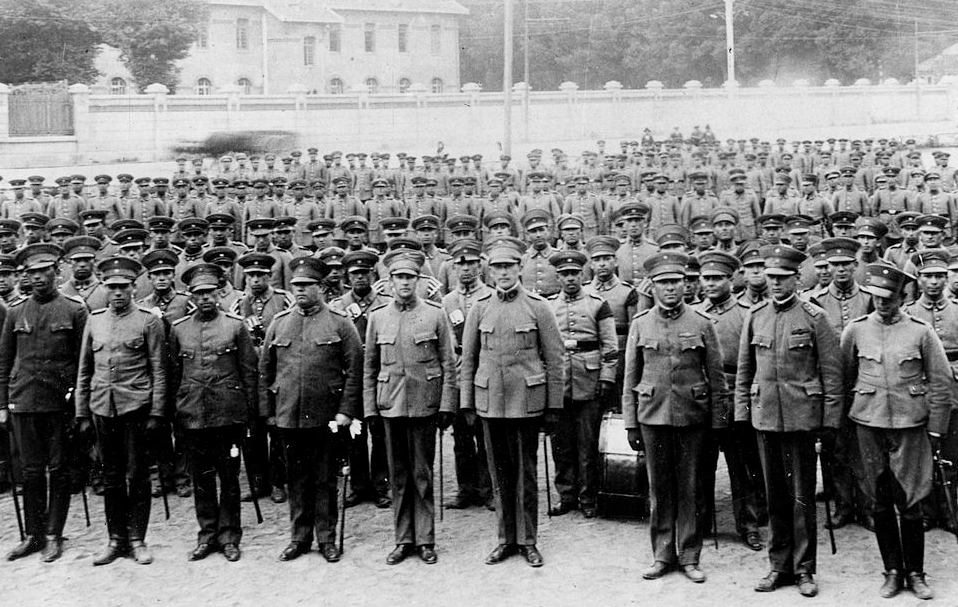

Edward Bomm and the other missionaries knew this day was coming. The bombings had begun several weeks earlier, with the first barrage falling just hours after the Japanese raid on Pearl Harbor. However, these preambles of war did little to prepare Ed and the rest of the team for the inevitable. The unnerving cadence of the Imperial Army’s victory march echoed throughout the streets of Manila.

The Japanese had arrived.

By the beginning of 1942, ABWE’s ministry in the Philippines was well-established. Founders Raphael Thomas and Lucy Peabody had planted churches and started Bible schools over a decade earlier. Ed and Marian Bomm had been serving on the island for seven years, with Ed pastoring the First Baptist Church of Manila and helping lead the 24-worker team.

Ed and Marian Bomm stand outside of the First Baptist Church of Manila, where Ed served as pastor until the Japanese occupation of the Philippines.

Once the Japanese overtook Manila in January, they tried to gain the people’s trust and cooperation by coercing their religious authorities.

On January 27, 1942 Ed and a group of 38 other ministry leaders from the Philippines, America, and Great Britain were told to attend a meeting at the Manila Hotel. They were forced to listen as a Japanese colonel delivered an oration touting the recent invasion as an act of deliverance from American oppression.

After being harangued, each man was asked to sign a pledge of loyalty to the Japanese.

Ed and two other men refused, which angered the officers. As the other men left, the three were pulled aside and harassed again. But the modern Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego stood their ground, aware they would face harsh retribution.

Unsurprisingly, Ed was the first ABWE missionary shipped to a detainment camp in Santo Tomás, his new home for approximately the next three years.

Santo Tomás was the largest internment camp in the Philippines, consigning a staggering 3,200 prisoners to scavenge for food and build their own makeshift shanties within its walls.

Shanties were arranged tightly together and were constructed from materials like bamboo and palm fronds.

Although subjected to repressive orders barked over loudspeakers, the prisoners were afforded a degree of self-governance. Internees appointed directors to oversee aspects of camp affairs including education, food, and religion.

Because of his faith, Ed stood out as a leader and was selected to run religious activities, like campwide Sunday services and weekly Bible classes. He was also chosen to be a floor monitor, overseeing 225 men. In a letter, he reflected on how guiding these men through “personal problems” offered a “rich experience,” opening doors for the gospel.

When three men escaped Santo Tomás and were later caught, the floor monitors were forced to watch their executions. Word of their deaths quickly spread throughout camp and deterred further escape attempts.

But the greatest threat to the internees was not the Japanese, who stationed minimal guards at the camp, but starvation. Food became scarce as the war raged on. The gardens failed to provide enough food, and canned rations gradually depleted. Watery mush made from corn and beans was considered a good dinner. Some people resorted to eating slugs and grass to alleviate their hunger.

“[We] have had dysentery, colitis, tonsillitis, dengue fever and many other dietary ailments,” later wrote Kay Friederichsen, an ABWE missionary held at Santo Tomás. She described the declining health of her two sons Bobby and Doug and husband Paul toward the end of their confinement: “Bobby had T.B. for a year…Doug is 20 lbs. underweight. Paul weighs 130 and I am 109. Just before deliverance we had to spend most of our time in bed from sheer weakness. We killed a cat for dinner the day before the army came in.”

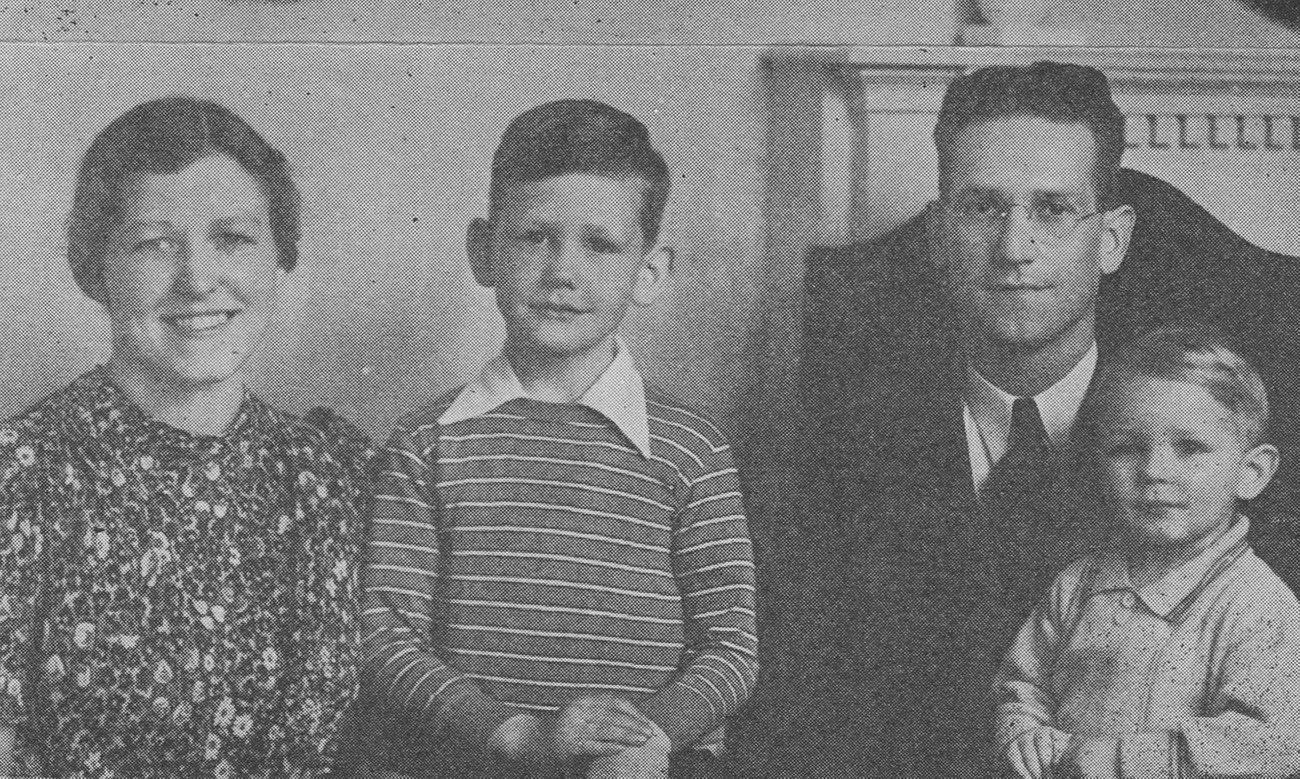

The Friederichsen family (left to right): Kay, Bobby, Paul, Doug

For two years, disease and malnutrition claimed lives each day, and many began to lose hope that they would see freedom again.

One ABWE missionary, Harold Palmer, died from an infection after a botched appendectomy while imprisoned.

But then on February 6, 1945, General Douglas MacArthur came to the rescue in a swift military campaign through the islands, and Santo Tomás was finally liberated.

Liberation day for each camp was not a peaceful event; the camps felt like war zones. Missionaries took cover from the gunfire as paratroopers descended and tanks smashed through fences. Ed and other internees were held hostage for several tense hours until the Japanese gave up and fled.

When Ed finally reunited with Marian after more than two years of separation, she was barely recognizable. Marian had been falsely accused of subverting Japanese authority and was forced into solitary confinement for 72 days, where she was abused and starved.

Upon liberation in 1945, 21 missionaries and their families returned to the US to recover, yet the Bomms remained in the Philippines.

The Bomms set to work rebuilding and reorganizing the scattered churches and destroyed Bible schools.

During 1941-45, Manila was destroyed by Japanese bombings and the subsequent Battle of Manila between US and Japanese forces. Photo credit: National Archives.

The team’s legacy of courage and faithfulness imprinted itself upon the hearts of Filipino pastors and churches, and in time, more than 1,500 churches and multiple Bible schools flourished across the island nation.

New Disease, New Ministry (East Pakistan: 1968)

Jeannie Lockerbie stared at the ceiling, trying her best to lie perfectly still. Quarantined to her bed, she could barely raise her head to eat.

The pain that had begun in her chest now spread over her liver and spleen.

Earlier in 1968, on her way back to East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) after furlough, Jeannie started to feel sick. She initially blamed the long journey and the sweltering heat and humidity for her growing fatigue. In her book Write the Vision, she later described the climate with words borrowed from British journalist Malcolm Muggeridge in his description of Calcutta, India:

“We arrived at the airport on one of those heavy, humid days for which Bengal is famous. The air seems to distill into water as one breathes it, and every movement costs one stupendous effort” (Guideposts, 1988).

As the days went by and Jeannie did not improve, the doctors concluded her sickness was not the result of weather; it was hepatitis.

The treatment: six weeks in bed.

But at the end of six weeks, Jeannie felt even worse, and more of her teammates had also fallen ill. This was an epidemic. Soon, only five out of the 35 ABWE missionaries remained healthy. Jeannie and others who were infected were confined to their beds for as many as 11 months.

With the long recovery time came the realization that they were not dealing with hepatitis, but rather an altogether new disease with varying symptoms. Abdominal pain, excruciating headaches, and fevers sapped the strength of those infected.

Yet as weeks and months of quarantine rolled by, the Lord was working out a greater plan—even through the pain and searing migraines. And Jeannie was about to see a part of it.

One afternoon, Jeannie heard a familiar voice in the hallway. Mrs. Basanti Das entered her room.

A schoolteacher by profession, Mrs. Das was working with Lynn Silvernale and the Bible translation team to produce a readable, Common Language Bengali Bible. During the visit, Mrs. Das noticed Jeannie’s bookshelf and marveled at the sight of the books.

“You have so much in English; we have so little in Bengali.”

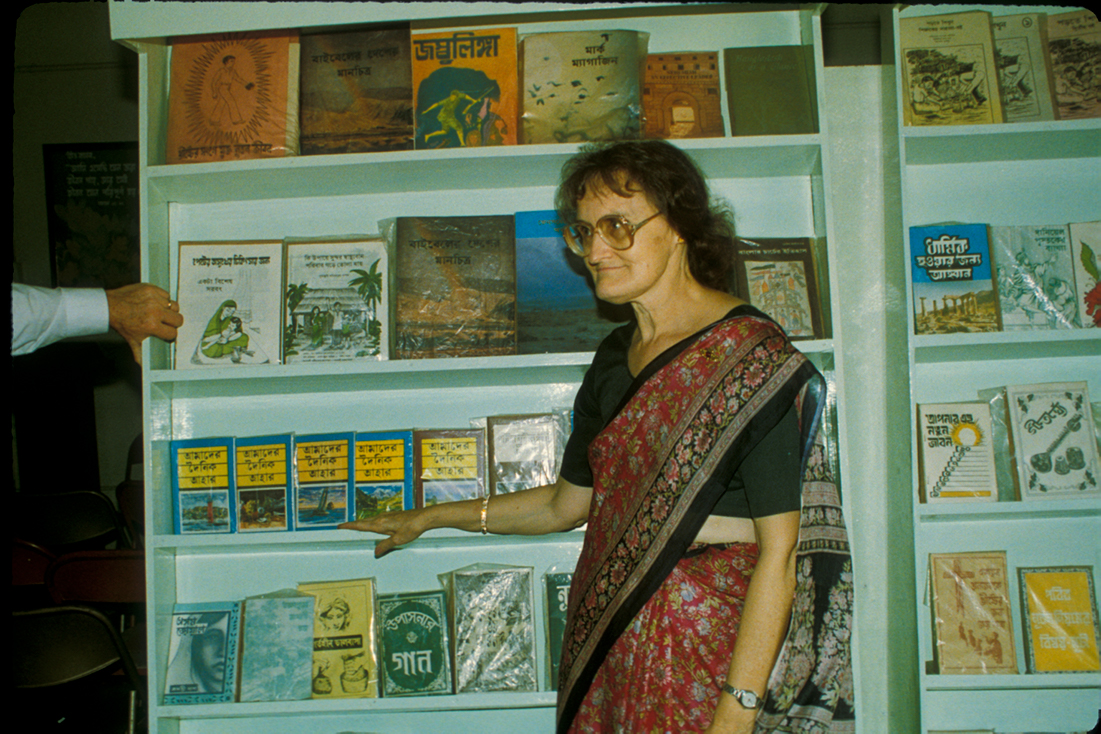

Jeannie stands in front of a bookshelf filled with some of the materials produced by the Literature Division, a ministry which she started after God used a serious illness to speak to her heart about the lack of Christian literature for Bengalis.

Jeannie latched on to those words. Even after two centuries of ministry work in South Asia by missionary giants such as William Carey and Amy Carmichael, the quantity of Christian literature in the Bengali language was scarce and difficult for common people to understand. Soon after her conversation with Mrs. Das, Jeannie stumbled upon Habakkuk 2:2: “Write the vision and make it plain.”

Jeannie knew something had to be done.

The verse compelled her to develop and open the Literature Division with the goal of translating and producing Christian materials in common language Bengali. Since then, the team of missionaries and local believers has written, edited, designed, and published hundreds of Christian resources: Sunday school curricula, Bible studies, reference books, children’s books, and much more.

Today, it still operates under Bengali leadership and direction.

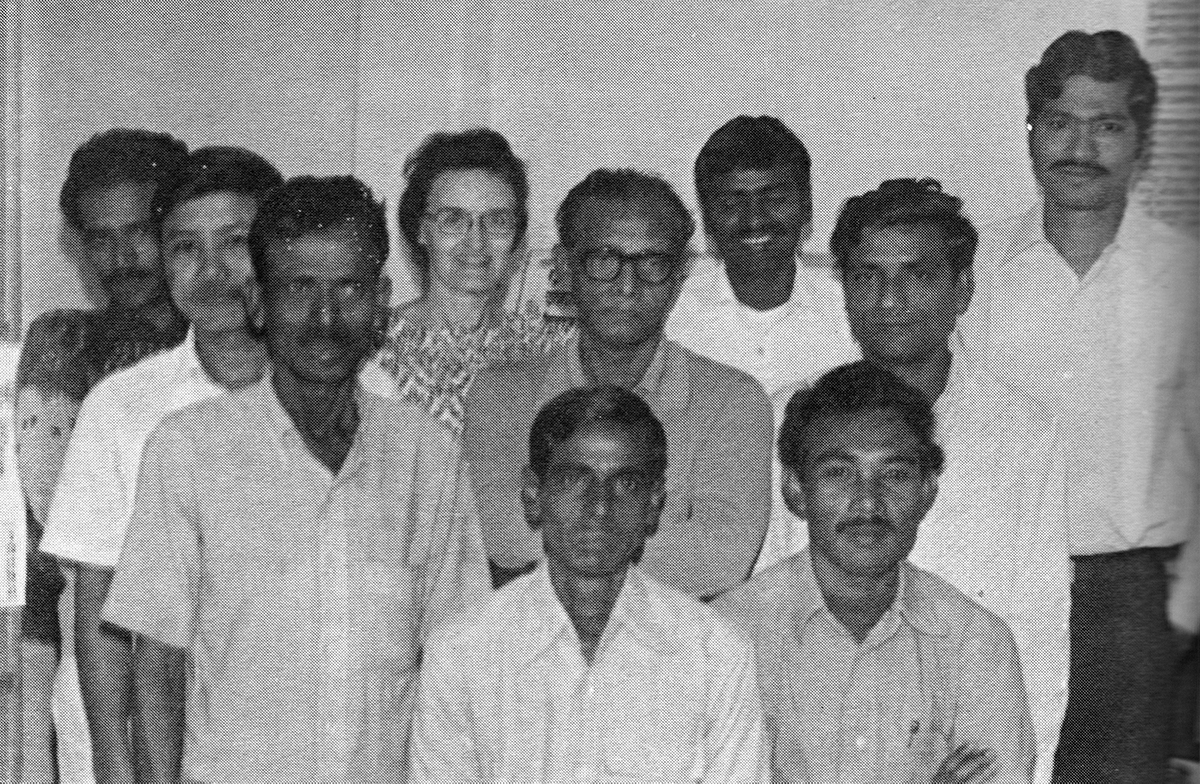

National believers joined the team and were critical in the translation and daily operations. Today, they lead the ministry.

But the formation of the Literature Division is just one of the handful of fruitful projects that came out of the epidemic. During that time, missionaries also started translating the New Testament into the tribal language of the Tripura people. When missionaries delivered it to the tribe’s leader, he said, “Now that we can understand the Bible, we have no excuse not to obey.”

Nearly a year elapsed before the missionaries recovered, and many had lifelong symptoms as a result. Jeannie herself spent nine long months in bed.

But 52 years later, she recounts the time with one word: “Blessing.” Were it not for the virus, it’s possible that many Bengali-speakers would not have any access to Christian books, biographies, study guides, and the Bible in words they can understand.

The “Other” 9/11 (Chile: 1970-86)

For decades, Chile shined as a beacon of democracy and political stability in South America. But that began to change in November 1970, when Salvador Allende won the presidency, becoming the first Marxist leader to capture a South American free election.

The following day, thousands of people—fearful of the new government—rushed to get tickets to evacuate the country.

At the time, ABWE missionary Larry Smith led a field team in the capital city of Santiago. They faced daily risks as American church planters living under an anti-Western government. Despite the obstacles, the team chose to stay, trusting that God was at work amid the tumultuous political climate.

For the next three years, Larry and his family received personal threats and intimidation.

“Rocks were thrown through our windows, and I was threatened to be killed by our neighbor who was a communist,” Larry wrote.

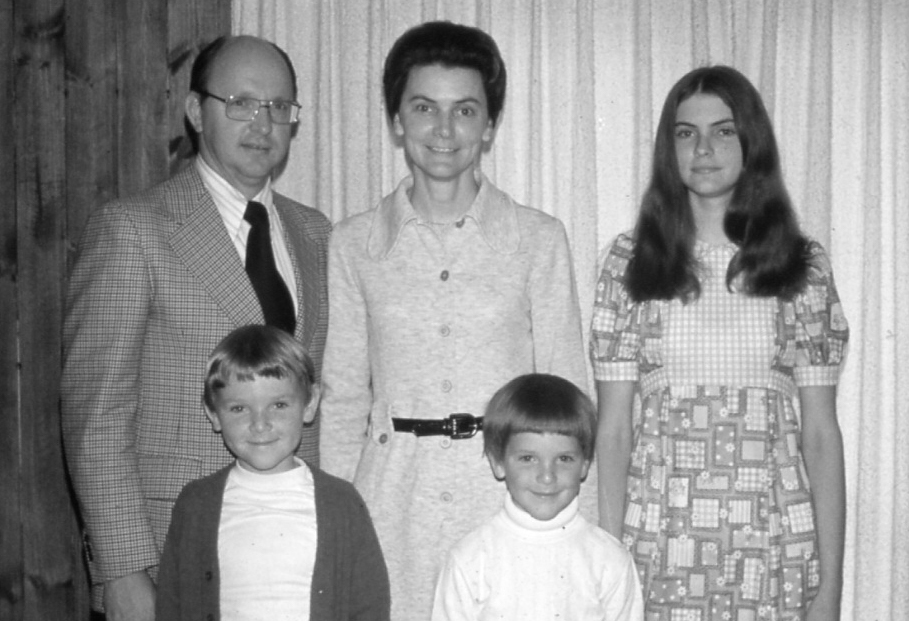

Larry Smith and his family faced threats and harassment from the government and their neighbors.

Informants advised Larry to take different roads to church as to avoid assassination, but Larry refused. “[I] continued as usual, in part to show I would not be intimidated by such threats,” he explained.

Larry was even accused of being a CIA spy. On one occasion, two armed officers showed up at his doorstep unannounced and interrogated him at gunpoint, investigating his supposed “illegal entry” into Chile.

A group of armed men even attempted to kidnap Larry by forcing him to drive his own truck as the getaway vehicle. But while starting the truck, Larry disengaged the manual choke to grind down the battery, causing the engine to sputter and buying him time so that someone could discover and stop the abduction. Eventually, the noise caused Larry’s neighbors to check out the commotion. Their plot foiled, the kidnappers abandoned the mission and fled the scene.

The economy faltered under Allende’s reforms and wage increases, which sparked an uncontrollable spree of consumerism that the economy could not keep pace with. Stores rationed goods to avoid scarcities, and Chileans turned to black markets for meat and other necessities. The middle class suffered the most.

“The country went on a downward spiral, with shortages of everything, even toilet paper.” Larry wrote. “There were riots on a daily basis, and worst of all, political division resulted in dislike or hatred toward those of the opposite viewpoint.”

The Chilean church was divided too. One Sunday, Larry heard an unpleasant grunt from the congregation as he prayed for the salvation of President Allende. After the service, he asked the woman who made the noise for an explanation.

“If Salvador Allende goes to heaven, I don’t want to be there,” she replied.

Salvador Allende held the office of president for three years before being overthrown in 1973. During the coup, he reportedly committed suicide with an AK-47 gifted to him by Cuban dictator Fidel Castro. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.

September 11, 1973 marked an abrupt end to Allende’s reign. Larry remembers the fateful day as the “other” 9/11.

A coup d’état, led by army chief Augusto Pinochet and backed by the US, deposed Allende and his left-wing allies in less than 24 hours, swinging the balance of power to the far right overnight.

Pinochet would rule with an iron fist for the next 17 years. It is estimated more than 3,000 people died in the aftermath of the coup as Allende supporters were arrested and executed.

Although the coup rescued the missionaries from the dangers of Allende’s government, the revolution only widened the fissure in the church. The missionaries’ initial support of the junta quickly eroded when they witnessed its horrors: tanks rumbling through the streets, fighter jets buzzing over treetops, and trucks piled high with dead bodies.

Pinochet’s liberation of Chile from Marxist rule had simply turned the country into an equally dangerous autocracy. He had no intention of relinquishing power and returning Chile to a democratic society.

Augusto Pinochet’s military junta seized power in 1973 and didn’t relinquish it until 1990. In its course, it committed a litany of human rights crimes, detaining up to 80,000 dissenters in concentration camps. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons.

However, as evil as Pinochet’s regime was, the church began to experience growth under his leadership, which welcomed the evangelical community.

The Smiths stayed in Chile for 13 more years, and Larry became known as the “before-during-after missionary” because he had remained on the field all through the crisis. By risking their lives, the team won the locals’ favor and trust, sowing the seeds for a great gospel harvest, according to Scott Russell, Executive Director for Latin America.

“It’s harvest time in Chile, and that means we need all hands on deck—because we only have so much time,” Russell said. “It won’t be harvest season forever.”

Chile is currently one of ABWE’s largest mission fields in Latin America. More than 30 churches have been planted, and Chilean believers have even formed their own missions agency, reaching more than 15 different countries.

Before and after the coup, Larry continued teaching at the Bible institute, now the Facultad Teológica Biblica Bautista, an ABWE seminary in Santiago.

Today, some 50 years later, it still raises up and prepare dozens of Chilean nationals as pastors and missionaries each year.

God Meant for Good

Romans 8:28 reminds us that all things work together for good. Yet missionary stories like these, as well as the story of Joseph, remind us what exactly “all things” entails. Joseph was sold into slavery by his own brothers, falsely accused by his master’s wife, and imprisoned for years. But God rewarded his faithfulness by placing him at the right hand of Pharaoh to rescue not only Egypt but his own family who betrayed him.

What men mean for evil, God means for good, even in the darkest hours.

“The Lord’s sovereignty reigns supreme, even when evil forces seem to be thwarting his plans,” said Paul Davis, ABWE President. “But God always means for good—whether that’s ministry growth in the Philippines, the creation of a publishing program in Bangladesh, or the survival of a very successful seminary in Chile.”

If history holds any lesson for today, it’s that God can do his greatest work in times of crisis.