Many of these theories are pervasive in sending organizations. Proponents of “movement” methodologies seek to start people movements—that is, to facilitate not merely a few individuals saved and discipled but whole neighborhoods, regions, and countries reached. Often, these methodologies prescribe a rapid pace.

It seems like a noble cause to aim to reach thousands quickly. But not all methods of evangelism and discipleship are equally biblical or healthy. Today’s topic examines one method, Four Fields (4F), which is related to the larger theory of church planting movements (CPM).

Four Fields stands in contrast with simpler approaches of proclaiming gospel truths faithfully. (These simpler approaches are called proclamation, God-centered, or church-centered models). Charitably defined, 4F seeks to replicate what Jesus and his disciples did in their ministries, by first entering a lost community, sharing the gospel, discipling the saved, and forming churches and leaders so that other Christians could reproduce this plan from entry to leadership formation.

The plan aims to equip believers to share the good news and start reproducing churches who make disciples and share with others, who in turn will repeat the plan. That plan depends upon an understanding of the four areas or “fields”: evangelism, discipleship, church planting, and leadership development (see the Four Fields of Kingdom Growth). These four fields of work are understood to be the definition of gospel ministry or kingdom work. In the words of Steve Addison, a proponent, 4F is an “overview of the principles and practices of a multiplying movement.” (For more details on 4F from the view of a seasoned CPM advocate, see the late Stephen Robert Smith’s, “An evaluation of Training for Trainers (T4T) as an aid for developing sustained church planting movements (CPMs),” pp. 38, 145-46.)

How should we evaluate 4F?

THE POSITIVES

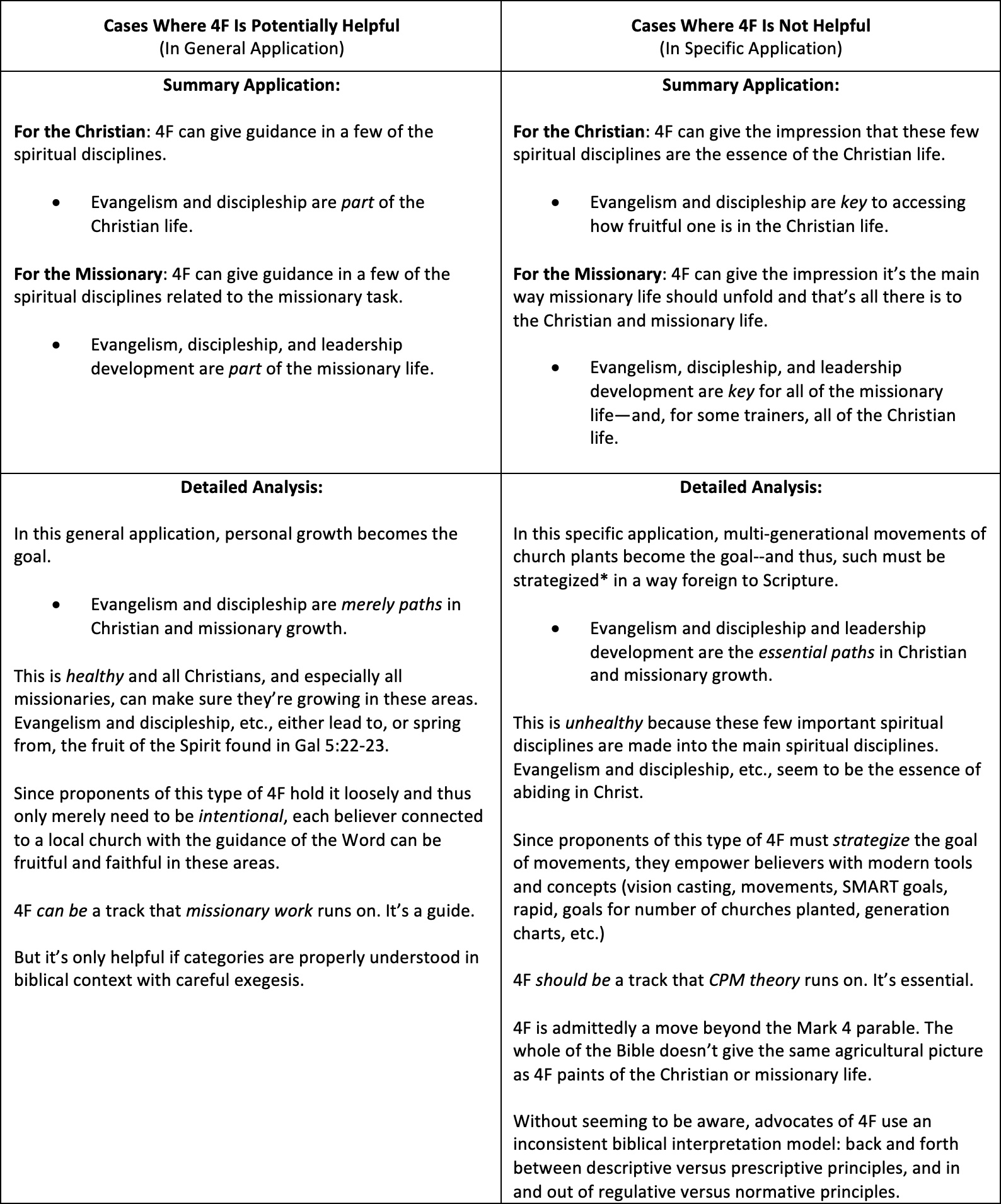

In my overseas ministry, I have been exposed to 4F theory for years. The chart below contrasts both the positives and negatives. In general, I am concerned about some of the baggage that is intrinsic to the model. But first, a few positives are in order.

In one presentation, Nathan Shank, a key 4F voice, says things that are wise and good. For instance, he affirms that we should not be setting goals for things we can’t control (such as conversions) because they are in God’s hands (18:45 time stamp). He states that God is the giver of new life (18:45). And he emphasizes the importance of putting the work in the hands of locals (22:00). (Also see Nathan and Kari Shank, Four Fields of Kingdom Growth, pp. 33, 104.) These are all true, necessary, and helpful nuances that are refreshing to hear from a movement-oriented practitioner.

THE CONCERNS

Despite these positives, there is reason to be cautious about 4F. We agree that the church is the vehicle of God’s glory (Shank, p. 3), and we agree on the value of turning the ministry over to nationals (pp. 34, 37, 40), but we disagree about the proper methods of church planting. That is because 4F shares many of the same assumptions of the larger CPM paradigm (pp. 102, 108). Let’s explore these concerns below.

Scriptural Foundation

Four Fields builds on the familiar Parable of the Soils in Mark 4:26-29 (Shank, p. 9). There is, of course, no problem with beginning with Mark 4:26-29—but this text hardly constitutes a framework for how we should see all of the Christian or missionary life. Rather, it provides a lens by which to understand why some hearers reject the gospel and others do not. The parable’s immediate application was to the first-century Jews who rejected Christ, and the passage remains relevant for evangelism today. But even if this passage were meant to provide an exhaustive framework of the missionary task, Shank admits that much of 4F is beyond the Mark 4 parable altogether (p. 17).

These outside additions include key features of CPM—movements, rapid multiplication, multi-generational work, dependence on goal setting, participative Bible studies, emphasizing training rather than teaching, exit strategies, an emphasis on the need for lots of converts. Each of these features has varying degrees of merit. Some are wise and helpful; others lead in the direction of pragmatism. Yet none of them has a specific textual basis in Mark’s Gospel or anywhere else in the New Testament.

Pragmatic Tendencies

Shank gives good cautions about over-reliance on numbers (pp. 104, 124, 133). Yet with 4F in general, too often numeric outcomes are equated with success. For instance, 4F can pit addition of disciples against multiplication, pitting one or two individuals being saved versus groups being saved (see 24:00 timestamp in this video; see also Shank, pp. 95, 101, 105). Yet in Acts 2:47 we are told that the Lord “added” to the number of those being saved.

While a 4F practitioner may not implement or even support all the objectionable traits of movement theology, I have yet to see 4F practiced without employing at least some of these extra-Scriptural elements.

Prescriptive or Descriptive?

In 4F, there are grave inconsistencies in reading Acts or the Gospels prescriptively or descriptively. A missionary may interpret Luke 10:6 prescriptively and seek a person of peace (without properly defining a “man of peace”), yet fail to consider why missionaries should not also follow Luke 10’s other instructions—healing the sick, treading on serpents, or not carrying moneybags. Similarly, when one looks closely at Paul’s first missionary journey, there are miracles and prophets involved that are hard to interpret as prescriptive for missionaries today (note the 8:02 time stamp of this video). Shank tries to address the problem (pp. 42, 141) but leaves many questions unanswered.

Why the inconsistency? When I’ve been in CPM trainings (almost always involving 4F ideology), often the trainers weave in and out of regulative and normative interpretative methods. The regulative principle means that we are bound to do only what Scripture commands, while the normative principle teaches that we are free to do something if it is not explicitly forbidden in Scripture. For example, the 4F emphasis on believers creating name lists of lost people for them to share the gospel with, and then holding all Christian members of a group accountable to share weekly (pp. 41, 44-46, 50-51, 56-57) is not directly from Scripture. We see witnessing and accountability in Scripture, but not accountability to share the gospel as 4F trainers advocate. Accountability in the 4F system is construed simply to be a rule applied to the Christian’s life to measure so-called obedience, defined almost exclusively in terms of personal evangelism. And yet these trainers frown upon other practices (such as a weeks-long class for church membership before baptism) because they are not in Scripture. Why adopt one practice not explicitly mandated in Scripture but repudiate others?

Admittedly, it’s nearly impossible to always stay in a regulative paradigm. But it is possible to acknowledge when we leave it. Yet I’ve never heard 4F voices acknowledge that they are weaving in and out of regulative and normative principles—or between prescriptive and descriptive readings of key passages.

Practically, this results in a dangerous over-emphasis on evangelism as the sole goal of the Christian life. Consider that nowhere in the Bible is any Christian ever held directly accountable how many times they have evangelized. Any time a single spiritual discipline is emphasized at the expense of all others, becoming the core of the Christian life, we are at risk of losing balance. Yet Shank appears to make this a foundation of his approach (pp. 6, 41, 46, 50, 57, 60).

CONCLUSION

Listen to 4F trainers to learn what you can. There are positive elements within 4F that both missionaries and everyday Christians may find helpful. But use discernment. As an overseas colleague recently wrote, “Four Fields is not anti-Scriptural, but I am not convinced that Paul was concerned with having a method in place like this.”

Conversely, a caution stands for those of us who aren’t proponents of 4F. It is good to be concerned with the effects of pragmatism, convert-counting, speed, and the like. Yet we must not find our righteousness in the slowness of our work, the smallness of our reach, or the lack of explosive results.

Even so, my biggest concern is that 4F exists primarily for missionaries discouraged by a lack of results, and there lies its greatest weaknesses. Just as our relationship with Christ does not operate according to a simple formula for rapid success, neither does the missionary task. Though 4F acknowledges God’s sovereignty over our work (p. 15), the 4F training manual lays out a plan (p. 27, 33, 41-43, 45, 95, 101, 105, 114) for how things can move rapidly (p. 30, 37, 122, 144, 146).

Scripture never tells us to start movements or to make them grow rapidly. Despite what 4F claims, it is not merely a suggestion (p. 3) but is seen as an essential tool (p. 5). Ultimately, the model attempts to prescribe in too much fine detail (pp. 35-118) what the missionary should do in each stage of ministry, and in this respect it fails the most to live up to careful study and application of Scripture.