Yet some slave systems date back to ancient China and before. They were even common among Native Americans before Columbus discovered the New World. Slavery has existed virtually since the dawn of recorded human history—since man first learned the perverse art of overpowering other men.

The problem is not merely societal but lies deep in the depraved human heart. For the missionary seeking to engage the world with the gospel message and see its fruit transform culture, then, the question is not why slavery existed—and still exists in much of the world today—but how so many cultures succeeded in abolishing it.

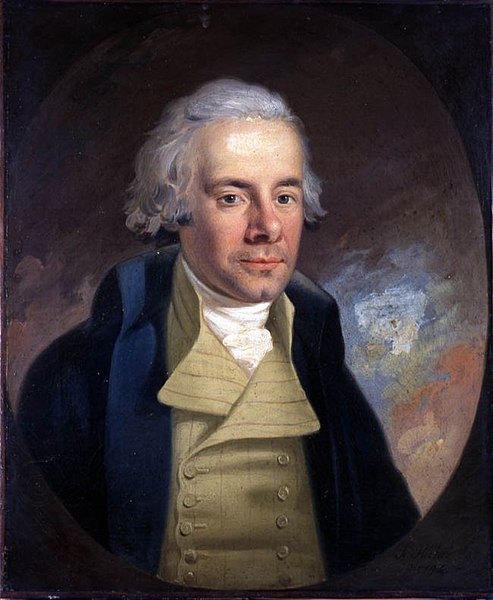

Today, on the 261st birthday of William Wilberforce, it is only fitting for us to direct our attention to the Christian statesman, British politician, philanthropist, missionary advocate, and abolitionist whom God used to topple the wicked slavery enterprise of his day.

Dizzying Heights

Wilberforce was born on August 24, 1759. He was beset with frailty from birth, suffering from nearsightedness and indigestion throughout his entire life. He never grew above 5’3” and weighed just 76 pounds as an adult during one bout with illness.

Although severe, these maladies never dulled his sharp mind or oratory. In grammar school, his teacher often propped him up on a table to read aloud to his classmates. At 10 years old, after the death of his father, Wilberforce moved in with his aunt and uncle in Wimbledon. It was in this season of life that, despite the waning influence of the church in post-Enlightenment England, Wilberforce encountered his family’s spirituality, living in a town which was the center of a Methodist revival. Wilberforce grew fond of Methodism, but his limited exposure to the evangelical movement afforded him too little time to fully embrace it.

Wilberforce’s relatives, who were also friends with George Whitefield, worried his mother, who retrieved him before he could be converted. But Wilberforce would carry these spiritual experiences into adulthood—and into his political career.

He secretly exchanged letters with his aunt and uncle, who had quickly become surrogate parents to him. But soon, worldly charms enticed the teenager, and the promise of fame and popularity due to his singing voice, charm, and wit drew his heart away from religion.

Wilberforce enrolled at the University of Cambridge in 1776. Ironically, his college experience was similar to that of today’s students, with limited study and excessive entertainment. He befriended students, as Wilberforce later put it, whose “conversation was even worse than their lives.”1 Yet even at this prestigious university, Wilberforce managed to distinguish himself from his peers. Thomas Gisborne, who lived next to him, commented, “There was no one at all like him. For powers of entertainment, always fond of repartee and discussion.”2

At Cambridge, Wilberforce befriended William Pitt the Younger. As Wilberforce’s match in public discourse, Pitt later became the youngest prime minister in British history. The wide-eyed pair often sat in the House of Commons, critiquing the ongoing speeches and debates among themselves. It was here that Wilberforce developed his love for politics.

Over the next several years, Wilberforce’s eloquence and rhetoric launched him into government, and he was elected to Parliament, representing Yorkshire county. His motivations at the outset of his political career were than less than selfless. He later admitted that his “own distinction was my darling object.”3 At just 24, with the recently elected Prime Minister Pitt as his close friend, Wilberforce evolved into a political celebrity of sorts, sitting in one of the most powerful seats in all of Parliament.

The Great Change

It was around this time during Wilberforce’s public ascent that God interrupted his life. In his diary, Wilberforce recounted this episode as “The Great Change.”

In the fall of 1784, Wilberforce vacationed to France with Isaac Milner, the brother of his old teacher. Milner would later occupy the Lucasian Chair in mathematics and chemistry, a position previously held by Isaac Newton and, in our own history, Stephen Hawking. He also achieved renown for co-authoring the multi-volume Ecclesiastical History of the Church of Christ with his brother.

Wilberforce and Milner conversed for hours across many topics, especially religion, on their continental journey. Milner, a devout Christian, spoke of his personal salvation in Jesus Christ. Wilberforce was surprised that someone as astute as Milner found the Christian worldview tenable. He looked up to Milner as a role model, and so his beliefs deeply affected Wilberforce. Ultimately, the Spirit worked through Milner to bring Wilberforce to saving faith. The rising politician felt convicted of his sinful lifestyle, “having so long neglected the unspeakable mercies of my God and Savior.”4

After his spiritual rebirth, the popular social escapades he once relished in were now repulsive to Wilberforce. He viewed parties of uncontrollable drinking and frivolous conversation as a distraction to his duty as a Christian politician.

But Wilberforce was not sure if he should stay in politics or pursue ministry. He wrestled with how his participation in such a morally corrupt environment as Parliament—where bribery, fixed elections, and open drunkenness were commonplace—could align with God’s will. Distraught, Wilberforce paid a visit to an old friend, an Anglican clergyman whom he had met while living with his aunt and uncle as a youngster. John Newton, the former slave-ship captain and the hymn writer who had penned Amazing Grace, was pleasantly surprised to find Wilberforce at his doorstep.

Newton encouraged Wilberforce to remain in Parliament and use his platform to shine light into the darkness of the slave trade. For the next 20 years, Wilberforce would act as a lighthouse to Britain, directing the empire away from its dark and evil course of the slave trade, becoming a beacon for other nations.

Wilberforce began championing a litany of charitable causes. At one point, he was backing 69 different philanthropic causes benefiting low-income families, orphans, and juveniles. He also assisted in starting parachurch organizations such as the Society for Bettering the Cause of the Poor and the Church Missionary Society. And although he had never been there, Wilberforce carried a passion to reach India with the gospel. But he is most known for his work advocating the abolition of the slave trade. He recounted how the gospel and the doctrine of the imago Dei had impressed his conscience:

“So enormous, so dreadful, so irremediable did the trade’s wickedness appear that my own mind was completely made up for abolition. Let the consequences be what they would: I from this time determined that I would never rest until I had effected its abolition.”5

The Road to Abolition

The fight against slavery was an uphill battle. Wilberforce needed to not only convince wealthy Parliament members, most of whom were benefiting financially from the institution, of the need for abolition, but he had to also educate a largely ignorant public who rarely interacted with African slaves. Wilberforce began with the latter.

In 1797, Wilberforce moved to Clapham with his family and formed what became the “Clapham Sect”—a group of upper-class and prominent Christians who campaigned for abolition. Part of its mission was to discredit the slave trade by using British newspapers to publicize accounts of brutality. Over time, the Clapham Sect published numerous letters and press releases of their findings, exposing the dark details of the infamous Middle Passage to the general public.

In one famous speech on the floor in the House of Commons, Wilberforce put forward an abolition bill and gave a grave report of the slave trade’s abuses. He concluded: “Having heard all of this you may choose to look the other way, but you can never again say you did not know.”6

Parliament did, however, ignore it. For over a decade, Wilberforce proposed abolition bills only to have each defeated. In the few occasions a bill made it past the House of Commons, it was squashed by the House of Lords. By 1805, Wilberforce’s motions had failed a total of 11 times.

Wilberforce received death threats and duel challenges from abolition opponents. He even broke ranks with dear friends, including Prime Minister Pitt. His health failed rapidly due to the strain. Seeking refuge from the dangers surrounding him, he often recited Psalm 119 on his commute to Parliament. Apart from the encouragement and support of friends like Newton, Milner, and the Clapham circle, Wilberforce would have given up.

Thomas Clarkson, a key ally to Wilberforce, organized a public campaign after the crushing defeat in 1805. His tour and the petitions it produced proved invaluable for the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which passed its first two hearings in the House of Commons—surpassing all previous endeavors.

The fateful day finally arrived on February 23, 1807. Virtually every Parliament member present was aware they were at a historic precipice, and many basked in the moment with flouring speeches to Wilberforce and his epic crusade. With victory imminent, the elderly Wilberforce struggled to maintain his emotional composure.

Finally, after ten long hours of debate, the solicitor-general concluded the floor speeches with his own closing words:

“When [Wilberforce] retires to the bosom of his happy and delighted family, when he lays himself down on his bed, reflecting on the innumerable voices that will be raised in every quarter of the world to bless him, how much more pure and perfect felicity must he enjoy, in the consciousness of having preserved so many millions of his fellow-creatures.”7

Wilberforce could not contain his tears any longer. They ran heavily down his ragged face as he trembled beneath the weight of the moment’s glory. An avalanche of praise erupted under the charged atmosphere. Members of the House rose to their feet and gave three cheers, and Wilberforce’s name rang through the legendary halls. The night culminated in a 283-16 vote in favor of abolition.

Final Years

The victory solidified Wilberforce as a hero. However, the humble man would have none of its accompanying recognition and kept quietly plugging away at legislation for other projects, enjoying the company of friends, and spending time with his family. Wilberforce refused to work on his all-important objects on Sundays, observing the Lord’s Day.

For the next 25 years, Wilberforce strived to guarantee the slave trade’s complete collapse as an institution. He gave much of his money to orphanages, leaving himself nearly penniless in his elderly years. In 1833, he received news of the emancipation of all slaves in the British Empire. Finally at peace, Wilberforce died three days later.

Today, Wilberforce is recognized as one of history’s greatest Christian cultural reformers. His contributions to civic morality, shaped by the gospel, radically transformed British society’s treatment of the “least of these.” His activism marked a pivot point in the direction of Western culture, such that today slavery is considered unconscionable in much of the developed world.

The power of God in the gospel equipped Wilberforce to spread common grace to a fallen world. His life serves as a reminder for believers—especially missionaries serving in contexts where Christian values are not yet embedded—that justice must be driven by the gospel and defined by Scripture. By God’s amazing grace, Wilberforce understood this truth, and the world is a much better place because of it.

1. Edward Gilliat, Heroes of Modern Crusades: True Stories of the Undaunted Chivalry of Champions of the Downtrodden, (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1909), 20.

2. Ibid., 20.

3. John Piper, Amazing Grace in the Life of William Wilberforce, (Wheaton: Crossway, 2006), 38.

4. James Henry Potts, Our Thrones and Crowns, (Boston: B. B. Russell, 1887), 340.

5. Christian History Magazine Editorial Staff, Mark Galli, Ted Olsen, J. I. Packer, 131 Christians Everyone Should Know (Nashville: Christianity Today, Inc., 2000), 284.

6. The Abolition Project, William Wilberforce’s 1789 Abolition Speech, https://www.st-andrews-anglican-calgary.ca/downloads/WilberforceSpeech1789.pdf

7. Sir Reginald Coupland, Wilberforce, a Narrative, (England: Oxford University Press, 1923), 341.