They listened to Jonathan Allen preach a rousing commissioning sermon. These were the first American missionaries to be sent out by the fledgling American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, then only two years old.

But what most surprised some that day was that two of the five new missionaries were women: Ann Judson and Harriet Atwood. And it’s clear from Allen’s sermon that these women were not viewed merely as luggage accompanying their husbands, but as important, personal contributors to the hoped-for mission among the Hindus and Muslims of India.

At one point in the sermon Allen spoke at length directly to these young ladies:

It will be your business, my dear children, to teach these women, to whom your husbands can have but little, or no access. Go to them and do all in your power, to enlighten their minds, and bring them to the knowledge of the truth. . . . Teach them to realize that they are not an inferior race of creatures; but stand upon a par with men. Teach them that they have immortal souls; and are no longer to burn themselves, in the same fire, with the bodies of their departed husbands. Go, bring them from their cloisters into the assemblies of the saints. Teach them to accept of Christ as their Savior, and to enjoy the privileges of the children of God.

Can women be sent as missionaries? From the earliest days of Protestant missions from North America, the answer has been a solid and unequivocal yes. And not just as wives of missionaries. While many did raise concerns about sending out unmarried women early on, that too was being done by the mid-1800s. Then, as now, the question was not primarily “can” but rather, “how.”

How should female missionaries contribute to the work of global missions?

In serious and valuable ways.

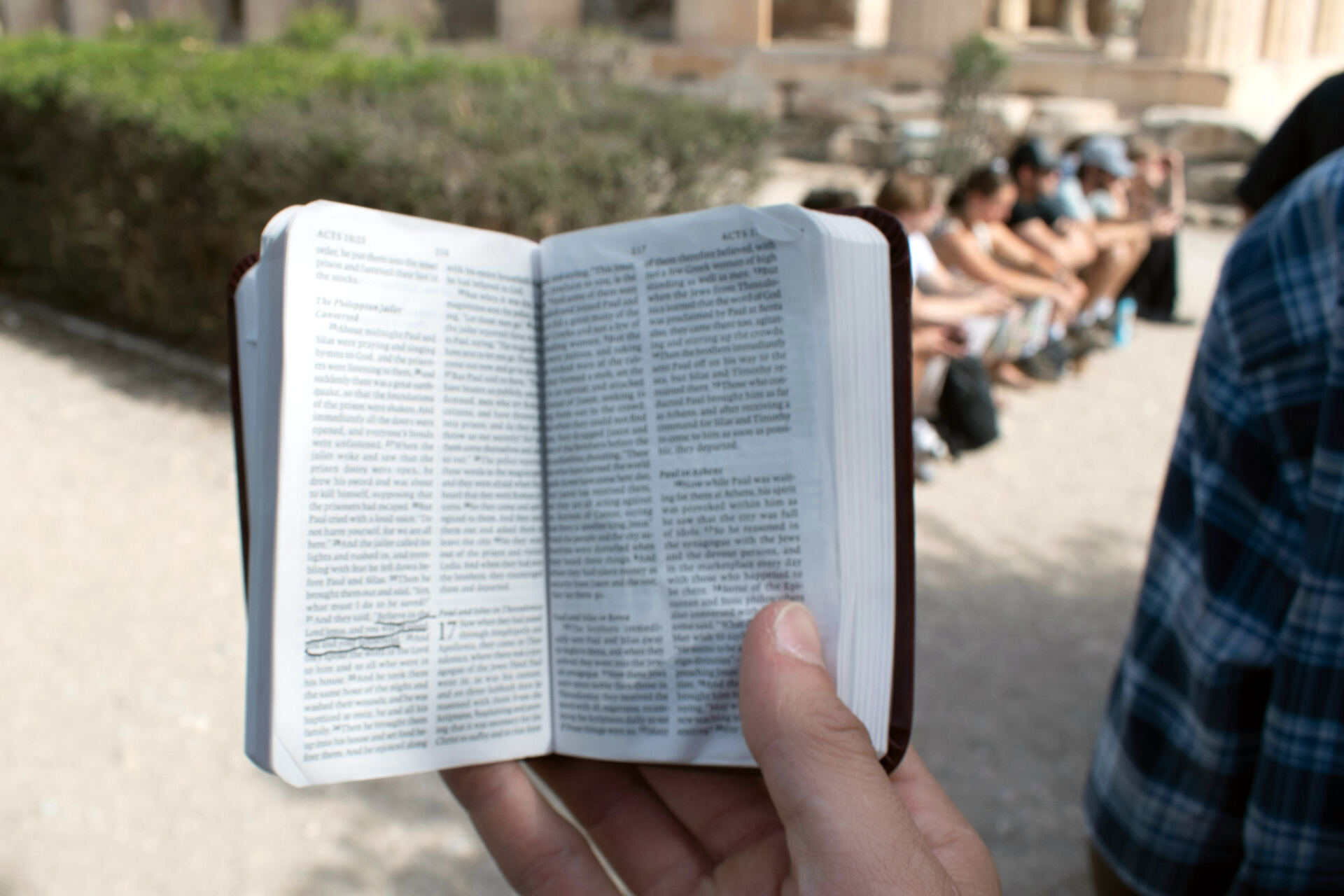

In this, the apostle Paul gives a helpful example. While clearly teaching on the priority of male leadership in the local church (1 Timothy 2:12), Paul demonstrated that this truth in no way diminished the ability of women to give important service to the work of the church. Perhaps one of the best examples of this is found in a passage many overlook, at the end of Paul’s supreme theological work, his letter to the Romans. In Romans 16:1 we read: “I commend to you our sister Phoebe, who is a servant of the church in Cenchreae. So you should welcome her in the Lord in a manner worthy of the saints and assist her in whatever matter she may require your help. For indeed she has been a benefactor of many—me also” (CSB).

Most agree that the meaning of this commendation is clear; the apostle Paul almost certainly entrusted the arduous task of delivering his letter to the saints in Rome to a trustworthy and admired woman, Phoebe. Thus we have Paul’s commendation of her to affirm the authenticity of her mission—once she’d traversed the 1,100 kilometers from Corinth to Rome in advance of Paul’s own hoped-for visit.

Paul goes on to instruct the Roman Christians to provide any needed support to help her, just as they would for him or any other missionary. Can women be entrusted with important tasks in the great work of global missions? The apostle Paul certainly seemed to think so, and we can read his Letter to the Romans today as evidence of the wisdom of his choice.

Differently, based on individual gifts, desires, and circumstances.

And yet, the example of women like Phoebe, or the intentional missionary devotion of women like Anne Judson, may also confuse us. Certainly single women sent out in the work of missions need a personal desire to give themselves to a specific gospel task. There will be some married women, like Anne Judson, who shared her husband’s passion for missionary service. Yet I think we may fall into a serious error if we conclude that every wife who heads overseas with her husband must desire to be a missionary in the same ways.

To illustrate this, let me pick an example closer to most of our own experiences. I hope you realize that the wife of every local church pastor, for example, isn’t necessarily a de facto (or actual) member of the church staff. That’s simply not a biblical expectation. Some pastors’ wives will have a desire and ability to have an active and public ministry in their church. They’ll lead other women; they’ll teach, disciple, counsel, and organize.

Other pastors’ wives—because of personality, preferences, or stage of life—will have much less bandwidth for such things and may be more focused on responsibilities closer to home. Yes, the pastor’s wife needs to be a faithful wife and church member. But that’s pretty much all. There’s no biblical office of “pastor’s wife,” and we do harm to both Scripture and women if we impose on them wrong-headed burdens found nowhere in the Bible. There are hundreds of different ways a pastor’s wife can serve and aid her husband’s ministry; precisely none require a formal, defined role.

But let’s say we send out that very same pastor as a “missionary.” Suddenly, we’re tempted to impose all sorts of extra-biblical expectations on his wife. I even know of mission sending agencies that actually think of themselves as “complementarian,” and yet they say a male missionary’s wife must have the same sense of “calling” to missions as her husband. I’ve even heard some say that she must be so committed that she would go as a missionary to their target people group even if she’d never married her husband.

Well, beyond just being objectively silly, this is a profound misunderstanding of what it means for a husband to lead his wife. Yes, by all means a missionary’s wife should be happily willing to follow him into the overseas life he’s leading toward. And it’s fine to ask whether either the husband or wife seem so constituted as to thrive in a foreign context. But that’s a far cry from insisting that every missionary’s wife must have a ministry calling equal to her husbands. Some, like Anne Judson, will have a desire to serve in a more external missionary capacity. Others will not.

So, yes, women—including the wives of missionaries—can be formal and active missionaries in their own right, but they don’t have to be.

By doing anything that biblical teaching on the local church encourages, regardless of location.

Christians looking to the Bible as their guide have, in the main, come to the same conclusion throughout the years: women can do anything in missions that Scripture encourages them to do in their own local churches.

The problem in all this arises mainly when folks begin to wonder if the biblical commands and wisdom given to local churches somehow evaporates the moment one steps onto the “mission field.” This notion is in no way limited to the question of women’s contribution to missions. It’s one of the great failings of evangelical missions in the world today. In almost every area of missionary work, well-meaning souls somehow conclude that because their gospel labor is far from their homeland and in a culture different from their own, then the clear teaching of Scripture can (and even should) be ignored—as if biblical teaching on elders, membership, local churches, patient instruction, and gender distinctions somehow evaporates during a flight from New York to New Delhi.

Again, this is not limited to questions about women. In almost every place that the Bible speaks to the organization of churches and gospel ministry, there are those who—in the name of contextualization or urgency or exceptional circumstances—find themselves discarding biblical teaching they would likely treat as authoritative in their homelands. The illogic of this principle is, I hope, fairly obvious, but that does little to diminish its influence.

In a context where new churches need leaders now, some conclude that the command—“Don’t be too quick to appoint anyone as an elder” (1 Tim. 5:22) can’t really be meant for their context. Or, in a place where opportunities for gospel expansion seem to abound, the command to do our ministry “with great patience, and careful instruction” can’t really be binding if it slows things down. So it should come as no surprise that the same mindset, in contexts where male leaders are rare or passive, might tempt us to ignore the command “not to allow a woman to teach or have authority over a man” (1 Tim. 2:12). But whenever contextualization or urgency or any other agenda becomes King, the Word of God naturally gets treated as its handmaid.

But there are also Christians who think the work of missions is urgent, and the opportunities great, and the value of women missionaries immense, but who also treat God’s Word as authoritative in every place, among every people, in every language, through all of time. I want to be one of those people, and I hope you do too. We want to be happily and hopefully committed to obedience to God’s Word about everything, even if that obedience would seem to hinder our desires for immediate, visible results.

So can women be missionaries? Yes, of course. But also yes to the biblical teaching on gender distinctions in the life of the church. The two are not at odds. Attention to this will do nothing to stifle the valuable role that women can play in missions. And it will do a great deal to keep us from letting new contexts undermine the universal authority of Scripture, wherever in the world we find ourselves.

Editor’s Note: This article originally appeared on 9Marks on December 10, 2019. Used with permission.