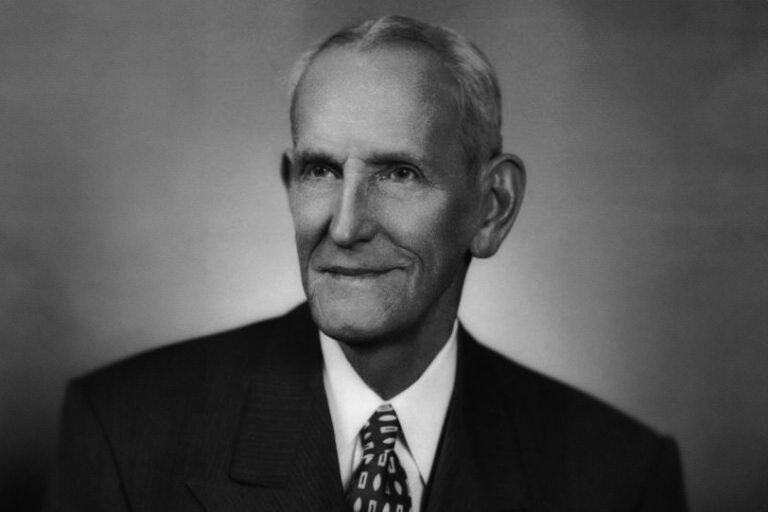

Throughout his missionary career in the Philippines, Raphael Thomas maintained a strong conviction that his medical work as a doctor should directly serve the mission of evangelism and church planting.

Educated in medicine and theology at prestigious schools in New England, Raphael determined from a young age that his life’s goal would be to serve as a medical missionary in Asia. Over the course of his ministry from 1904-1948, he directed a hospital and multiple dispensaries, actively shared the gospel across the Philippine islands, developed student ministries, and founded an evangelistic institute to train Filipino leaders. When he was prevented from fully integrating evangelism into his medical work, he and a small group of missionaries and US-based supporters united to found the Association of Baptists for Evangelism in the Orient—later renamed ABWE.

The following excerpt from Jim Ruff’s newly released biography of Raphael “Raph” Thomas portrays his initial months in the Philippines as he explored remote regions to determine strategic locations for ministry.

Editor’s Note: In pursuit of historical accuracy, Mediko draws from multiple primary sources, including Raphael’s own writings. Original style conventions have been retained, as well as some outdated terminology, out of respect to the original work.

In July of 1905, Raph experienced another highlight of his first term: an eighteen-day exploratory trip to the extreme south of Negros Island. His fellow-missionary Charles L. Maxfield (1872-1935), who arrived in the Philippines in the same year as Raph, described what he titled as “A Colportage Wagon Tour” in a letter to friends and supporters in America. The party consisted of 5 students from the Baptist dormitory, two colporteurs, a cook and the two missionaries. They visited the towns and villages along 70 miles of the sea coast and then went inland to visit towns along the foot of the mountains.

The colportage wagon had been supplied by friends of Mr. Maxfield in America, and two local ponies provided the horsepower. On either side of the wagon, messages had been painted. On the one side, in Visayan, was written Ma-ayong Balita, and on the other side, in Spanish, the phrase Las Buenas Nuevas. Both phrases declared the purpose of their trip, to declare “The Good News.” Maxfield remarked that to the children the jingling bells and the “novel American wagon” were comparatively of as much interest as Barnum’s circus would have been to American children.

While they stopped for only an hour or so in some villages, in each village, in only a few minutes, a gathering of the people would provide a good hearing for the preaching of the Word of God. It was Holy Week, and most of the people from the farms were gathered in the towns and villages for the processions that would form in the evening. If they preached in the evenings, after the processions, an audience “of a thousand or more” would be available in some places.

They sold nine hundred printed editions of the Gospels, thousands of tracts, and many English and Spanish Bibles. The faith of the ministry team was increased by both the desire to hear, the eagerness to buy, and the “intelligent questioning” of the people with regard to “the Way of Salvation.”

Mr. Maxfield’s description of the work of Dr. Thomas, his colleague, provides an early view of the physical care and spiritual concern Raph lavished on those he met.

Dr. Thomas not only healed bodies but he drove the arrow of conviction for sin to many hearts and applied the balm of the Gospel to the wound. Believing as he does that the disease of sin is more deadly in its effect than sickness of the body it is not surprising that he often went beneath the surface and made plain the fact that much of the sickness was due to disregard of the laws of nature or disobedience to the laws of God. Even better than the medicines given were the wholesome hygienic talks given at the clinic and many who care for medicine were made to see that vicious habits were destroying both body and soul. And many who had but a little while longer to live were guided to the Great Physician. Believing as he does so much in the Great Physician, we can feel not less confidently that he left many of his patients happy in Christian hope.

He added that even larger towns were without a doctor, and there was little knowledge of sanitation and hygiene. Contagious diseases and plagues were “almost as fatal to children as was the edict of Pharaoh.” The need for a medical missionary was great!

Raph had already decided to give a large part of his time to touring in a similar way through “the four districts of Panay, Conception and northern and southern Negros.” Maxfield admitted that such a ministry would be hard on the body, but there was no question about the need of such work. He estimated that they could reach all the large places in those districts, ministering to the needs of two hundred thousand people in thirty days. During the eighteen-day trip he was describing, twenty-three hundred people were treated “and nearly every kind of sickness and disease from slight fevers and pulling teeth to the setting of a broken arm was considered.” Maxfield expressed his joy that “each of the fields in the islands may have the presence of a medical missionary” during an annual tour. He closed the letter with an admission that more families were needed to reach out to over two hundred thousand people, and the hope that more families would soon come.

Raph was determined to know of ministry possibilities throughout the region in which he was to serve. Below, he describes an early investigation of the island of Mindanao. After describing a hair-raising experience at sea, Raph tells of an encounter with the Moslem residents, frequently called Moros at that time, who were the ancestors of the Muslims on Mindanao today.

Before the hospital in Iloilo was erected, however, I felt the urge to see more of the medical possibilities elsewhere. I discovered that Mindanao held those who used the Visayan language, and I was wondering if my call might lead me there, or at least lead others there. I also wished to bring back some young man who might be trained for service there later. This I was able to do, but never was able to persuade our Board to go in and “possess the land,” which would have been possible I believe at that time. I had sampled the medical work in Capiz and found it satisfactory. I now wished to investigate Mindanao, the second largest island in the Archipelago.

Eventually I caught a Transport that was journeying south. I say “eventually” purposely as it was recognized that ships rarely sailed on time. Transports were especially desirable, as they took missionaries at a dollar a head: most convenient method. It was appreciated. We finally started and arrived en route at Cebu. From there I took a side trip to Mactan, close by, where Magellan was massacred. It was a quiet spot, and there was a small monument to commemorate his death, but how inadequate for such an event. From there we sailed south to Mindanao, to Camp Overton, on the north shore. The day before I landed I was informed an American soldier had been attacked by a Moro, who had sneaked up on him unawares. He saved his rifle by discharging it and thus summoning help, but the Moro hacked off his hand. The commander of the post was courteous, and I was permitted to go to the west coast in a launch. Once there I journeyed about, healing the sick and looking over the territory, with occasional jaunts by canoe thru the mangrove swamps.

Editor’s Note: This excerpt is taken from chapter seven of Mediko: The Life and Legacy of Dr. Raphael Thomas, Medical Missionary to the Philippines by Jim Ruff. Used with permission.